The Galeto snack bar in Lisbon opened in 1966. It remains open and there are still many places like Galeto in Lisbon and Porto, monuments to the last decade of Portugal’s long dictatorship, when the winds of change were starting to blow and the regime suddenly looked less than eternal. Galeto, in one word, was modern: a long counter rather than tables to accommodate an anonymous clientele of office workers and, on the menu, sandwiches rather than bacalhau. The horror.

Alex Fernandes begins his account of the Carnation Revolution, the military coup that overthrew the Estado Novo on April 25, 1974, in Galeto a year earlier. Two Captains in the Portuguese army, then fighting an increasingly brutal colonial war in Africa, sit at the counter discussing what should be done. Disgruntlement and conspiracy are spreading among the lower ranks of the army. Twelve years after the start of the war and with the odds of a decisive victory increasingly disappearing, the Movement of Captains is bent on revolution. “To Angola, and in force,” dictator Oliveira Salazar told the Portuguese public in 1961. Now it was time to leave Africa, and in force.

What kind of dictatorship was it? Predictably, there is no agreement in Portugal on this question. There were political prisoners, almost certainly tens of thousands over fifty years. Torture was used. Assassinations were uncommon by the standards of other dictatorships, with even far left historians placing them at something like two hundred and others opting for a lower figure. Although censorship was institutionalised, it often took a surprising turn. I remember browsing through my family’s books as a child and finding a copy of Sartre’s The Nausea. The book was in fact published in Lisbon in 1958. A more obviously political tract could not be published, but the censors likely made little sense of it. Whether the regime deserves to be called fascist remains a matter of intense disagreement. Some have called it a “university fascism,” a reference to Salazar’s academic background as a Coimbra professor, which coloured his demeanour to the very end. Fernandes stays away from these thorny matters.

If in the metropole state violence was carefully managed and mostly stayed under the surface, the “Africa war”, as it was known then, quickly became a deadly affair. Close to 10,000 Portuguese soldiers lost their lives. The number of victims on the African side is estimated to be close to 100,000, including in such gruesome massacres as Wiriyamu in Mozambique, where in just one day in December 1972 Portuguese commandos killed hundreds of villagers accused of hiding enemy guerrillas.

The Carnation Revolution reads like a political thriller, making good use of the endless material provided by a coterie of colourful historical characters and events. Fernandes, a Portuguese writer living in London, deftly conveys what a madcap enterprise the revolution truly was, while showing how it was able to succeed in spectacular manner. History has a way to exceed the imagination of even the most farfetched political thriller. Fernandes has full command of the literature and historical archives on the revolution and his narrative deploys a level of detail few will find fault with.

What the book lacks is the necessary political and historical reflection on those events. Growing up in Portugal in the wake of the revolution — born just three months before, I can boast of knowing what it is like to live under fascism - I might have once agreed with the approach. Events in Portugal often seemed parochial and insignificant, valuable only for their unique picaresque character. Today the Carnation Revolution has acquired for me a much larger significance.

There is, first, the link between democracy and decolonisation. What the Portuguese revolutionaries understood was that dictatorship served a very specific purpose: to preserve the global empire Portugal had held for five centuries and around which it had built its identity. Democracy, which together with modernisation had become an imperative, would not be possible unless we let go of the empire. France struggled with the same question in Algeria: preserving French democracy and keeping Algeria were incompatible goals. Today, in Russia, it is clear that democracy will have to wait for a revolution in how the country sees itself, a revolution not too different from that which Portugal went through in the years before 1974. Democratizar, Descolonizar, Desenvolver. They formed a single whole. Democratise, Decolonise, Modernise.

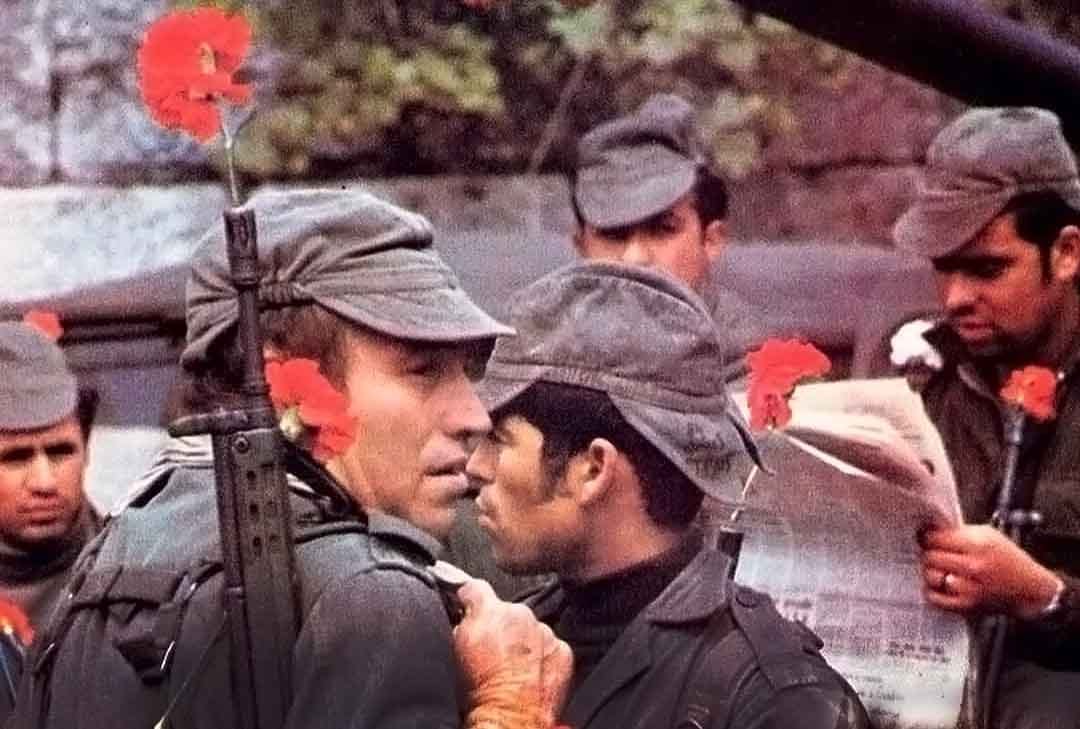

The other historical lesson of global relevance is on political utopia. Malraux, the accomplished French writer, Culture Minister under de Gaulle, liked to say that he loved Portugal for its “political unrealism.” There is a lot of that charming unrealism in The Carnation Revolution. On 25 April, 1974, when Captain Salgueiro Maia led a convoy of armoured vehicles to downtown Lisbon, many of the weapons had no bullets in them. At one point the convoy of tanks passes a cleaning lady at a restaurant holding some carnations to hand out an at event. One of the soldiers slides a carnation into the barrel of his rifle. Other soldiers follow suit and the rest is history. The signal for the revolution was a song broadcast over the radio. For a while the revolutionaries debated which song to pick, as if the matter at hand was a high school ball. When the convoy arrives at the outskirts of Lisbon, at sunrise on April 25, Maia feels the jeep stop. He waits for a few seconds, then asks: ‘What’s the matter?’ ‘Nothing, sir, just a red light,’ replies the driver.

By the time the convoy reaches the ministries in Praça do Comércio, it has become obvious that the government forces will offer no resistance. Any strong sense of loyalty has been eroded over a decade of change in the metropole and war in the colonies. That at least is the most common explanation for why everything was over so easily and so quickly. Fernandes shows that there were other factors, from Maia’s cunning to the presence of large crowds filling the Lisbon streets and squares. In that sense, April 25 was more of a revolution than a coup. A few hours later, Marcello Caetano, who succeeded Salazar in 1968, formally surrendered. Only four people, four young protestors, lost their lives. Later reports indicate that the agents who opened fire on the civilian demonstration were firing into the air.

Willy Brandt called the Carnation Revolution a “gentle revolution.” Newsweek called it “gentlemanly.” Brandos costumes or gentleness is regularly presented as the Portuguese national trait. There is some truth to it, but I think it is better seen as a sense of irony or aloofness, Malraux’s unrealism.

One year later, the country found itself verging towards a communist revolution, with the militant left proposing to replace the burgeoning electoral democracy with direct ”popular rule.” Henry Kissinger famously thought Portugal was lost to the Soviet bloc, more evidence of his sharp analytical powers. Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, one of the revolutionary leaders, was attracted to Cuba. Others such as future European Commission President Barroso became fully committed Maoists. America had Woodstock. We had the “Hot Summer of 75.” By 1976, the fever was subsiding, but not entirely. My parents tell me that, aged two or three, I insisted on walking the streets of Porto singing The Internationale. “This is the final struggle, Let us gather together, and tomorrow, The Internationale will be the human race.”

For a long time stories of the revolution, alternatively silly and sobering, rubbed me the wrong way. Surely this was not a serious country or a serious people. Today I have a very different opinion. What a collective demonstration of political wisdom the Carnations Revolution was. It was not unrealism but acute political realism, the capacity not to take political ideas too seriously. Different countries place their sense of reality in different things. For the Portuguese, political ideas, and perhaps ideas more generally, are not very real. What Portugal has shown over the past few decades is the ability to keep oneself sufficiently aloof from ideologies, including liberalism, which we now know can easily become its own form of fanaticism. Irony, a child of the Enlightenment, still lives in Portugal.

A half century has passed, a somewhat painful date for the children of April like myself. It feels like yesterday. Today, looking at Europe and the world from the Cais das Colunas in Lisbon, it often feels that everyone is drunk and we are alone, that the whole world has gone mad and we alone kept our wits.

(Shorter version here.)