Few other concepts are so mysterious or at least paradoxical. The Indo-Pacific was invented as a precursor to a great movement of Asian self-affirmation against Western imperialism and yet it is used today as a tool of American and European geopolitics. No country has done more to act as an Indo-Pacific power than China and yet it is China that most vehemently objects to the term. These are just two paradoxes. There may be others.

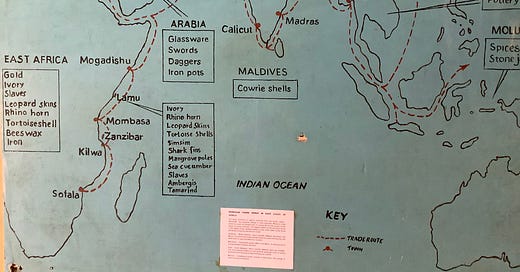

There is no doubt that the notion of the Indo-Pacific has anti-colonial and anti-Western roots. This is proven by both logic and historiography. Evidently, the idea that the Indian and Pacific littoral forms a unified geography refers back to the period before European hegemony when Arab, Indian, Malay, and Chinese traders were part of the same economic system. It was Europe that was peripheral. And the Indo-Pacific also points forward to a time when this vast region will no longer be divided from the outside as its different elements relate primarily to the Western centre.

Karl Haushofer, who coined the term, had a very clear understanding of these facts. In a seminal essay he discussed how the “monsoon countries” formed a single natural unit, organized around the age-old cultures of India and East Asia. That the largest concentration of mankind had fallen under European control was surely a temporary phenomenon. Germany could even play a role in their emancipation as it could gain from the disappearance of the colonial empires held by its European rivals. Haushofer was writing a century ago. We are free, he said, “of proprietary interests in those parts of the world.” Just as many contemporaries failed to sense the shift from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic during the Age of Discoveries, it is inevitable that the West will fail to see that the Indo-Pacific is regaining its weight “after 400 years of pillage and exploitation by colonial robbers.” (Die Einheit der Monsunländer, 1924).

We now arrive at the first paradox. Why has the Indo-Pacific become a tool of American power? It happened this way, I believe. When the late Shinzo Abe spoke of the confluence of two seas in a famous speech in 2007, he no doubt had in mind something not so different from Haushofer. The end game was to move the Indo-Pacific to the center of world politics, but he faced the difficulty that at present a greater unity and development of the Indo-Pacific region can only be attained on the basis of Western, liberal principles and rules. There is no other framework upon which to build a large area of economic integration and development. In this framework China would remain an outsider.

The second paradox suddenly becomes more intelligible as well. China may dream of bringing the Indo-Pacific into being, but it opposes the concept of a liberal Indo-Pacific. The Indo-Pacific for the authorities in Beijing is a project belonging entirely to the future, something to be created by Chinese power as it slowly expands outside its borders.

Reading this column and last one on Ukraine I noticed that both China and Ukraine are very historical projects.

China: "The Indo-Pacific for the authorities in Beijing is a project belonging entirely to the future, something to be created by Chinese power as it slowly expands outside its borders."

Ukraine: "There is the connection to the past and the vivid sense of an open future. For Ukraine the question is how to take control over fate and not to flinch in the face of the abyss."

And how different, but yes with significant similarities. Super interesting.

Another irony that has often bugged me. A "woke" America culturally appropriating the Indo-Pacific while figuratively removing the Asians from the Asia-Pacific. When Asians - like Abe - use the term, they are reclaiming their power and centrality from colonialism. When Americans use it, it is to claim a privilege despite being a non-regional actor. This might sound harsh but I think it is not unlike the use of the N word.